Is global warming melting one of

Africa’s best-kept secrets?

Biologist Nate Dappen calls attention

to the ‘Snows of the Nile’ in

a new documentary.

BY Tim Collie

PHOTOS BY Nate Dappen, ph.d. ’12, and Neil Losin

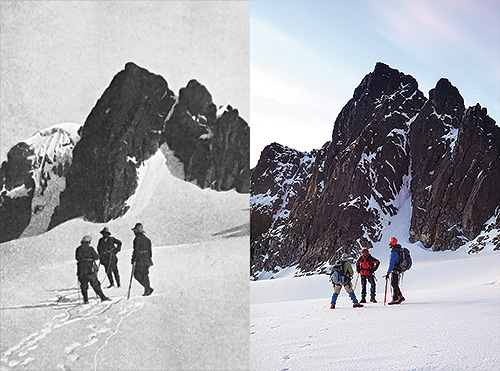

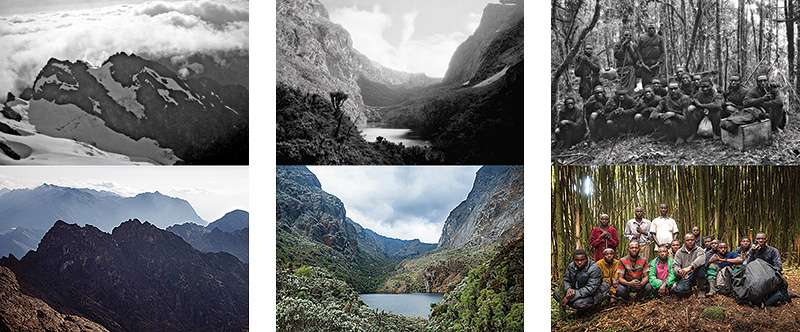

From top left, In April 1906 the Duke of Abruzzi, an Italian mountaineer, embarked on the first successful summit of the famous tropical glaciers of Rwenzori. Vittorio Sella’s photographs of the expedition created a sensation. In 2013, Nate Dappen, Ph.D. ’12, and Neil Losin re-created many of Sella’s shots, including this one of Mount Baker, to document a century of environmental change.

Nate Dappen, Ph.D. ’12, grew up among explorers.

His father was an “adventure doc”—a young physician who signed on as the medic on mountain-climbing expeditions around the world. An uncle was an outdoor journalist who would carry the family along on remote hiking, rafting, and rock-climbing assignments. And Nate Dappen’s mother, according to family lore, is one of the few women to ever canoe the entire Northwest Passage.

So when this University of Miami graduate decided to climb one of the world’s most remote mountain ranges to make a documentary about climate change, he was treading a well-worn family path. His father, in fact, had climbed these same mountains when the family lived in Kenya during Nate’s childhood.

The result of the younger Dappen’s 12-day expedition with filmmaking partner Neil Losin is Snows of the Nile, a 20-minute documentary that details their January 2013 odyssey to bring back a visual record of how global warming is thawing out one of the world’s least understood regions: the glacial Rwenzori mountains of equatorial Africa.

Snows is the work of a start-up filmmaking venture that has so far produced projects for the World Wildlife Fund, the National Science Foundation, and other organizations. “We really wanted to tell a climate change story that hadn’t been told before,” explains Dappen, who arrived in Miami in 2007 to begin a Ph.D. program in evolutionary biology. “We came up with this idea of visiting these tropical glaciers and using the historic photos taken of them a century ago to show the change due to global warming.”

Yes, there are glaciers in Africa. Known as the “Mountains of the Moon” or the “African Alps,” the Rwenzoris sit on the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Soaring to more than 16,000 feet at their highest point, the perpetually fog-shrouded mountains comprise a remarkable number of microclimates that extend from pristine rain forests and massive bogs to alpine wetlands, lakes, and streams that form the headwaters of the Nile.

1906 explorers can be seen standing on ice dozens of feet thicker than the ice seen in a 2013 re-creation featuring Losin, right, and two guides. Black and white images ©Fondazione Sella, Italy, courtesy DecaneasArchive.com

“It’s an extremely unknown place,” says Dappen. “As a biologist, being in that place was just incredible, a privilege. If you kill a mosquito that’s biting you there, it’s probably a mosquito that’s never been studied before. It’s one of the only places in the world where black leopards exist. It’s one of the few places in the world that has the one-horned unicorn chameleon and three-horned chameleon.”

Dappen and Losin formed their company, Day’s Edge Productions, after meeting in Costa Rica in 2008 on a graduate biology field course. Both were avid still photographers who quickly realized they shared a passion for filmmaking and storytelling. Though each had planned to pursue traditional academic careers, they were growing increasingly enamored with the idea of using their scientific backgrounds to make documentary films.

“Neither of us had made films before, but a few years after meeting we made our first short science film,” says Losin, who has a Ph.D. in biology from UCLA. “They weren’t good at first. But we’re both very competitive. Any time Nate did something, I wanted to do it better. Any time I did something, he wanted to do it better. And that helped us improve our craft.”

After a number of smaller efforts won awards, the pair began scoring contracts with organizations like the World Wildlife Fund to make films ranging from “trip documentaries to research profiles to hard-core research films,” notes Dappen.

Losin initially had the idea of shooting tropical glaciers to document climate change. Funding proved difficult until he and Dappen submitted their idea for the Rwenzori film to the “Stay Thirsty Grant” contest sponsored by the beer company Dos Equis. Much to their surprise, their project won the inaugural $25,000 Stay Thirsty Grant, presented by “The Most Interesting Man in the World,” the company’s popular pitchman.

From left, disappearing glaciers are part of a bigger story. Dappen and Losin saw how climate change affects the lives and livelihood of the Bakonjo tribe, many of whom serve as expert climbing guides and porters. They pose proudly, far right, to help re-create Sella’s 1906 photograph of their forebears.

In 2013 Dappen and Losin embarked on a tightly scheduled 12-day expedition to the remote African mountain range. It was Greek astronomer and geographer Ptolemy who first wrote about the Rwenzoris, theorizing how their snows were the source of the Nile. It wasn’t until the 19th century, though, that the range was explored. First described by Sir Henry Morton Stanley (of Stanley and Livingstone fame) in 1889, they were later photographed for the first time in 1906, during an expedition led by the Duke of Abruzzi, an Italian prince who was a mountaineer and explorer, and the photographer Vittorio Sella.

That journey, with its detailed logs and stunning photographic archive of the then-massive Rwenzori glaciers, would form the basis of Dappen and Losin’s narrative. The two wanted to retrace the duke’s trek, and photograph the range from the exact perspectives and angles of the glaciers Sella had captured more than a century ago.

Once on site, their strategy proved particularly difficult to enact, but not in the way they expected. After several days, they saw that the perspectives from which Sella had shot no longer existed. The glaciers and snowpack had melted so much in the intervening century that Dappen and Losin were now standing on rock hundreds of feet below where Sella had stood to make his shots and looking at peaks with much smaller snowcaps.

Dappen, left, and Losin continue pushing the limits of scientific exploration while inspiring others to care about our planet.

“It’s unbelievable how much ice has melted off there,” Dappen says. “The places where we were standing would literally have been under hundreds of feet of ice in 1906. Standing 300 or 400 feet lower, you’re just not going to recapture the same perspective ever again.”

Combining scientific context like this with original storytelling is what Dappen and Losin hope will set them apart in this new generation of documentary filmmaking. Like all filmmakers, they are contending with both the promise and demands of working in different platforms: the Web, TV, even interactive apps. Snows of the Nile, called “beautiful yet troubling” by National Geographic, has screened at numerous film festivals and can be seen online at www.snowsofthenile.com.

For Islands of Creation, their latest movie, which was funded by a National Science Foundation grant, Dappen and Losin turned to a familiar subject, J. Albert C. Uy, associate professor of biology in UM’s College of Arts and Sciences. Uy, a speciation expert who holds the Pat and Jeff Aresty Chair in Tropical Ecology, looks at how new species emerge in isolated environments like the Solomon Islands. Both men served as postdoctoral researchers in his lab. Uy granted the pair access to film his work because he felt that, as science Ph.D.s, they’d bring understanding and discipline to telling the story of his research.

“From the moment they approached me it was easy to agree because we were on the same page. You knew these were guys who would prioritize the science over the entertainment value,” says Uy. “They know exactly what it is to be a field biologist, so they weren’t going to be a hindrance. I was confident that it would be a positive collaboration.”

For his part, Dappen says one of his main goals is simply to make sure every film is better than the last. “I’m not so naïve that I think you can make a single film about a topic like climate change and change a lot of minds,” Dappen says. “But if you tell a good story, have good visuals, show people something they haven’t seen before, then I think you can start to make a difference.”

Follow

Follow