Mixing activism with architecture,

two University of Miami professors use drones to map informal cities in Latin America

in the hopes of improving conditions there.

By Robert C. Jones Jr.

The children play soccer barefoot on a dirt field, and when they aren’t imitating the flamboyant striking and passing skills of their country’s greatest footballers, they roam neighborhood streets, playing other games or sometimes just looking for something to eat.

If not for the efforts of a woman named Julia, many of them would go hungry. A 50-something community elder with an energetic spirit, Julia helps keep their bellies full, working with a group of other women to prepare meals that feed as many as 100 kids a day.

Life in some parts of Las Flores, a 5-square-mile shantytown near Barranquilla, Colombia, often presents a multitude of challenges. Food can be hard to come by; sewage, water, and electrical systems are nonexistent in most areas; and residents build shotgun-style homes with whatever materials they can find—in this case, mostly wood.

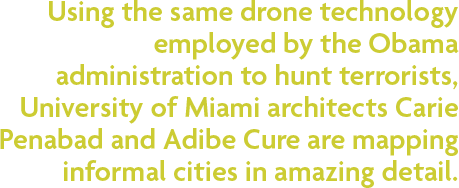

The local governments where slums like Las Flores are located see these places as eyesores, electing to leave them off of official maps. But two University of Miami School of Architecture professors, Carie Penabad, B.Arch. ’95, and Adib Cure, B.Arch. ’97, believe slums should not only be recognized but also given the assistance they need.

So with tools as simple and archaic as pencil and paper, and as advanced and high-tech as camera-equipped drones, the husband-and-wife team have made it their mission to map some of the poorest and most vulnerable places in the world.

They started in 2006, using traditional surveying techniques to map the slum of Shakha near Mumbai, India. The following year, they traveled to the Cape Town, South African township of Langa to map the informal settlement of Joe Slovo, one of the largest slums in that country. “Then we realized something,” recalls Penabad. “We’re based in Miami, and we’re traveling to the other side of the world to study these informal settlements, when, in fact, we have at our doorstep Latin America and the Caribbean, where an urban, informal population is growing. So why not turn our focus closer to home?”

And they did, beginning with Las Flores. Every spring semester between 2008 and 2015, Penabad and Cure have taken architecture students from their upper-level design studio and, starting two years ago, software engineers from UM’s Center for Computational Science, to this 60-year-old settlement to map its 75 neighborhood blocks and seven barrios. While CCS engineers operated the drones that produced highly detailed aerial maps of Las Flores, Penabad, Cure, and their students walked the streets, studying the slum’s building and construction patterns, peering into its simple wood and clay brick homes, observing neighborhood social interactions, and talking with some of the 10,000 residents who live there—all as part of an extensive effort to help cure what ails it.

“When these cities that are literally off the map are documented and studied, you begin to not only understand them but get a much bigger picture of their problems,” says Penabad. “Where would it make the most sense to bring in water and sewer lines? Where are they disconnected in terms of transportation? Where would it make the most sense to build a medical clinic? The potential for progress becomes more tangible and possible when you can see everything mapped out.”

X-RAY OF THE CITY

Penabad compares the maps to “X-rays that allow us to diagnose a settlement’s condition.”

Here’s what their “X-ray” of Las Flores shows: Newer barrios where small houses with sheet-metal roofs are built so close together that hardly any light and fresh air penetrate; older districts where, over time, wooden houses have been replaced by concrete homes; a scarcity of public gathering spaces; and unpaved streets.

Las Flores is compact, mirroring on-the-grid Barranquilla only in having a clearly delineated pattern of streets and blocks. “Houses come up to the edges of streets,” explains Penabad, “and there aren’t many automobiles, so people walk or bike to get to where they need to go.”

Nicki Gitlin, B.Arch. ’15, documented the streets of Las Flores, Colombia, as a student in the Informal Cities studio.

And usually where they need to go is to the larger metropolis to work in factories and hotels. Some of the women toil as housemaids. “Grandparents and children are most prevalent during the day, when the men and women are at work,” says Penabad, adding that Las Flores and many other such slums are surprisingly sustainable.

“There’s a well-structured network of families,” says Cure. “Older, more established families usually become the leaders, creating day care centers and micro businesses that help the community.” One woman, he notes, even started a mobile clothes-washing service, wheeling a portable manual washing machine door to door.

“Everyone living in an urban slum isn’t necessarily worse off,” says Justin Stoler, an assistant professor of geography and regional studies in UM’s College of Arts and Sciences, whose own research on informal settlements has taken him to Accra, Ghana, to explore links between neighborhoods, the environment, and human health. “Living in a slum has been shown to hinder growth but also sometimes to aid it via tight-knit communities that offer better resilience for overcoming stressors and communities where residents take care of one another and provide buffers from all the problems they’re dealing with on a daily basis.”

But media stories don’t often report on the resilience of these communities. Usually it’s the bad news—like crime or residents’ poor health and educational outcomes—that grabs the headlines, Penabad laments.

“Some people feel these settlements should be cleared out and bulldozed and the inhabitants relocated, but that’s the wrong thing to do,” she says. “Once these individuals are displaced, not only is their rich community life fractured, but they’re banished to the outskirts, usually far from the city center, which is where they make their livelihood.”

Improving the infrastructure within—from installing water and sewer lines to providing electricity and introducing public transportation routes—would do more to help slum dwellers than any relocation effort would, says Cure. But such public works-style projects require funding, not to mention the even greater task of convincing local governments to pour money into areas they don’t even include on formal maps.

Residents of Las Flores have been lucky in that the private sector has funded electrical and water projects in isolated areas of their settlement. But more improvements are needed, such as an urgent care clinic and a large banquet-style hall where community elder Julia and the other women with whom she works can feed the scores of children they cook for.

And that just scratches the surface.

To that end, Penabad and Cure’s students have taken to the drawing board to propose projects that could help ramp up Las Flores’ infrastructure.

BIKE TAXI STOPS AND STREETLAMPS

Residents taking bike taxis to work and neighborhoods with no street lights were among Nicki Gitlin’s first observations of this Colombian shantytown when she helped map it over a year ago as part of the Informal Cities studio, which requires students to conceive of and design a project that fills a critical need in the community.

“Lots of bike taxis, but no bike taxi stops,” says Gitlin, B.Arch. ’15. “And without streetlamps, some of the neighborhoods aren’t safe.”

So Gitlin, who has since graduated from UM and is now working for an architectural firm in New York, designed a single apparatus to solve both problems—a bike taxi stop that converts into a streetlamp at night. She also came up with a way residents could take an active role in improving their city, developing a GPS system that would operate through bike taxis.

Another student, once he arrived in Las Flores, saw opportunity in the settlement’s proximity to the Magdalena River. Already an income and food source for local kite fishermen, Colombia’s principal river could, with the implementation of a local water taxi system, become an important transportation route, taking residents from the water’s edge to the center of Barranquilla, where many of them work in the service industry.

The extension of Barranquilla bus routes into Las Flores, homes built with better ventilation, and a local fishery are among the other ideas UM students proposed.

“Small projects,” says Penabad, “large implications.” But only if their maps fall into the right hands.

TOOLS OF EMPOWERMENT

That is why, after the completion of every mapping exercise, Penabad and Cure give copies of the maps, accompanied by data and statistics, to government officials in the hope that the settlements will be incorporated into the larger formal city.

“Informal settlements aren’t going to disappear,” says Penabad. In fact, more than 800 million people live in slums worldwide, according to the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). In Latin America and the Caribbean alone, at least 24 percent of the region’s urban population reside in slums.

Maps of these informal settlements, Penabad, Cure, and Stoler agree, can provide a powerful case for inclusion.

“Great things can happen when you put communities on a map,” says Stoler. “It legitimizes them. Many slums are typified by informality. People are doing work that’s not on the books, that’s informal in nature, and often the government doesn’t recognize these areas and doesn’t even count the people. When suddenly you put boundaries around them and create maps, you’re further legitimizing their existence. You’re saying, ‘Hey, this community is now on the map just like all the other communities the government acknowledges, and these people matter too.’

“By mapping these communities in increasingly better detail,” continues Stoler, “you create a digital infrastructure that becomes the cornerstone for deploying actual infrastructure. Decision makers are less likely to consider putting in new electrical lines or extending the pipe water network into a neighborhood unless there are clear boundaries and a defined constituency.”

The maps also can make governments aware of potential new economic markets and the enterprising spirit of the people who live in slums, like the community elder on Santa Cruz del Islote, the most densely populated island on Earth. During a 2015 mapping exercise of that islet, where more than 1,200 people inhabit a piece of land off the coast of Colombia that’s roughly the size of a baseball field, Penabad and Cure learned of a woman’s efforts to raise donations for solar panels that were eventually installed on some homes.

Stoler, who for the past 12 years has been studying slums in West Africa with a team of researchers from universities across the nation, also encountered his fair share of enterprising shantytown residents during the considerable amount of time he spent in Ghana’s urban slums. While conducting research on drinking water needs in Accra, he met a young man who was starting his own business as a bagged-water supplier.

“He was living in a slum in a little shack with a couple of machines,” Stoler recalls.

Five years later, the UM researcher returned to Accra and tracked down the young entrepreneur, discovering that he had become a successful businessman with a modern factory and dozens of machines.

“People living in slum communities are as smart and resourceful as anybody anywhere else, and they are often forced to be creative to make ends meet,” says Stoler. “Their ability to adapt is amazing. So why wouldn’t local governments want to harness that work ethic, that creativity, that resiliency? And that’s why we should keep mapping.”

Looking like a giant insect with its four legs extended outward, the quadcopter sits in the center of the dirt road, its propellers beginning to spin faster and faster.

In Las Flores, a small group of curious youngsters gathers around, while just a few feet away Chris Mader, director of the software engineering core in the University of Miami’s Center for Computational Science (CCS), flips the switch to a remote-control device, sending the camera-equipped drone skyward with the speed of a rocket blasting off from its launchpad.

The aerial mapping of this shantytown near Barranquilla, Colombia, has begun.

“Robots that fly” is how Mader describes the drones he and CCS colleague Amin Sarafraz have been using to help two University of Miami School of Architecture professors, Carie Penabad, B.Arch. ’95, and Adib Cure, B.Arch. ’97, map informal settlements in Latin America.

Initially Penabad and Cure mapped the settlements on foot with pencil and paper, using traditional surveying techniques and satellite images that were not always clear. After they learned about CCS’s flying robots, though, their methods for mapping slums literally took flight.

Flying a programmed grid pattern at 15-to-20-minute intervals, with a GoPro camera attached to its underbelly, a single drone can map a 5-square-mile shantytown like Las Flores in about two days, according to Mader, who has traveled to Colombia with Penabad and Cure as a member of their mapping team.

The 600 to 800 high-resolution digital images captured by the drone are used to produce a highly detailed composite photo showing an aerial layout of the entire city—from rooftops and foliage to streets and even and trash piled up in backyards.

“For mapping small areas like informal settlements, drones are ideal,” says Mader. “They can fly closer to the ground [the drones Mader uses typically fly at an altitude of about 130 feet], they’re inexpensive, and it’s technology anyone can use.”

The drones have significantly reduced the time it takes to map a settlement. That doesn’t mean Penabad and Curie have abandoned the personal side of their research. They still walk shantytown streets, but only to gather the information drones can’t, such as the stories told by the inhabitants of some of the poorest and most vulnerable places on Earth.

“There may be 200 children under the age of 10 living in an informal city that’s not being serviced by any medical facility,” says Penabad. “The maps can show us where a medical clinic or school can be built.” Among the other questions that can be answered: Are there boundaries within slum neighborhoods? Where does the slum stop and the formal city begin?

Penabad and Cure’s goal is to make UM a center for the collection of data on informal settlements throughout Latin America. “We’ve found a way to map these in a pretty distinct way,” Penabad explains. “We’d like to acquire enough funding to deploy this toolkit more systematically and make it entirely open-sourced mapping.”

Follow

Follow