How the University of Miami became a game-changing

authority in identifying, treating, and educating

the public about sports-related brain injuries.

An avid sports fan who grew up in Canada, Gillian Hotz loved the brawling physicality of ice hockey. Yet as a young research neuroscientist who came to the University of Miami in 1992 to study traumatic brain injury at Jackson Memorial Hospital’s new Ryder Trauma Center, she was stunned by her first high school football game. Even sitting up in the stands at Harris Field in Homestead, where the powerhouse Miami Southridge Senior High Spartans played, she was unnerved by the violent, relentless THWACK! of helmet and shoulder pad colliding. “These were big, fast, strong kids, and I couldn’t believe how hard they were hitting each other,” Hotz recalls of that night in 1996 when she accompanied the team doctor, Lee Kaplan, then an orthopedic resident at UM/Jackson, and now director of the University of Miami Sports Medicine Institute, to the game. “And they were doing it again and again. I said to Kaplan, ‘This is crazy! These kids are killing each other.’’’

Not one to ignore a potential health or safety issue, Hotz returned to Jackson and cornered neurologist Kester Nedd, who was the director of neurorehabilitation at Ryder. Hotz urged him to start a clinic for mild traumatic brain injuries—which is what concussions are—for high school and other athletes.

“There were 35 high schools in Miami-Dade County, and I knew some student-athletes who got their heads knocked ought to be looked at before they returned to play,” says Hotz, founding director of the KiDZ Neuroscience Center at The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, part of UM’s Miller School of Medicine, and director of the Concussion Program. “But we didn’t know much about concussions then, and the culture was to shake it off, and get back into the game.”

Her intuition would prove prophetic. Today, concussions are considered a major public health concern, and there is growing awareness they should be treated for what they are—an injury to a vital organ. Caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head, concussions disrupt how the brain functions and can alter it permanently. But they are invisible injuries and weren’t on the nation’s health radar until National Football League players began suing the league for ignoring the growing evidence that multiple concussions put them at high risk for what’s been called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). As depicted in the 2015 film Concussion, the progressive neurodegenerative disease is blamed for the premature neurocognitive decline and deaths, including a number of suicides, of dozens of NFL players.

Hotz’s nearly quarter-century crusade to change the culture of ignoring concussion, which included the passage of a state law barring concussed youth athletes from immediately returning to play, has made Florida, and particularly Miami-Dade County, a safer place for contact sports. And it all began that night in Homestead, when she enlisted Kaplan and Vincent Scavo, then Southridge High’s athletic trainer, to her cause. With their support, the University of Miami has become home to one of the nation’s most comprehensive multidisciplinary programs for concussion diagnosis, treatment, education, training, and research.

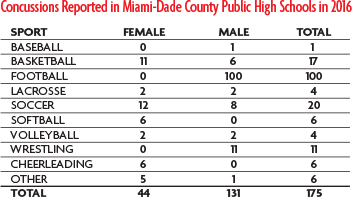

Now part of the University of Miami Sports Medicine Institute, which Kaplan launched with Scavo in 2008, the concussion clinic Hotz and Nedd established at Jackson in 1996 manages about 800 sports-related concussions a year. About 200 of those are high school athletes (mostly football players) from Miami-Dade County Public Schools, which partnered with UM in 2011 to establish the nation’s first countywide concussion testing and monitoring program for all high school students who play contact sports.

Given its reputation and experience, UM’s concussion program also has attracted several multidisciplinary concussion faculty and millions of dollars in concussion research grants from an array of organizations, including the NFL, General Electric and Under Armour for their Head Health Initiative, the military, and the private sector. Two of the grants come with the tantalizing prospect of revolutionizing concussion diagnosis and treatment.

The newest grant is for the development of a pill derived partly from the cannabis plant that could provide the first clinically proven concussion medication. The other is for a portable assessment device, a pair of computerized goggles that can objectively, accurately, and quickly diagnose concussions on the sidelines or in the locker room.

“We know that if we diagnose concussion and intervene early, the long-term consequences can be reduced,” says Michael E. Hoffer, professor of otolaryngology and neurological surgery who joined Hotz’s team in 2014 after spending much of his 21-year U.S. Navy career treating head injuries. “Both the diagnostic device and the pharmaceutical countermeasure are very exciting for these reasons.”

Research on the cannabinoid pill is still in the preclinical stage but, backed by serious funding, is promising. Last year Scythian Biosciences Inc., a Canadian company, awarded Hotz and a team of other neuroscience experts and researchers at The Miami Project and the Miller School $16 million to test a compound that they hope will reduce brain inflammation and the immune response, halting the cascade of symptoms many concussion sufferers endure.

Initially, common symptoms can include headache, blurred vision, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and confusion. Some people briefly lose consciousness. Over time, depression, anxiety, irritability, and mood swings can set in. Most, however, recover within two weeks.

But according to the 5th International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport held last year, symptoms in 10 to 20 percent of sports-related concussion cases persist for weeks, months, even years. With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating as many as 3.8 million sports-related concussions in the U.S. annually, that’s a huge population at risk for long-term effects.

The proposed medication combines cannabidiol (CBD), a major but non-intoxicating constituent of the cannabis plant, with a chemical that disrupts cannabinoid nerve-cell receptors. Naturally occurring in the human body, cannabinoid receptors are part of our endocannabinoid system, which is involved in appetite, pain sensation, mood, and memory.

If the compound, which should be in clinical trials next year, proves successful at halting concussion symptoms, it could help clinicians manage what is considered the most complicated sports-related injury. Concussions are so difficult to diagnose and treat because you can’t see one on an MRI or CAT scan and, like snowflakes, no two are alike. The symptoms vary and evolve rapidly, depending on the severity of the injury and the stage of the disruption to brain function.

“Concussion is not one disease; it’s a spectrum,” says Nedd, an expert in managing concussion symptoms. “You have to understand how the brain is organized and, when it’s injured, how that organization changed. You have to properly classify that before you start treatment.”

Too many community doctors, he notes, intervene too late and with the wrong treatment at the wrong time. “The patients say, ‘I have a headache,’ so you give them a pill for the headache; they say, ‘I can’t sleep,’ and you give them a pill for sleep. Then they say they are anxious and depressed, and pretty soon you don’t know if the pills are causing the problem, or the brain injury.’’

The goggles, known as the I-Portal PAS—portable assessment system—are familiar to most UM athletes, including those in club sports, because many volunteered to help Hoffer and his co-principal investigators test and refine the devices. Hoffer, Carey Balaban of the University of Pittsburgh, and Miller School graduate and otolaryngology resident Mikhaylo Szczupak, B.S.A.E./M.S.A.E. ’12, M.D. ’15, received grants from the Department of Defense and the Head Health Challenge II, which is funded by the NFL, GE, and Under Armour, to conduct the tests.

The goggles are equipped with two 3-D cameras that each sample one eye’s movement at 100 frames per second—much faster than the human brain processes images. As a result, they can detect abnormal eye-reflex responses, which indicate subtle balance and visual deficits. The goggles essentially enable clinicians to see what they’ve never seen before: a concussion.

Developed by Neuro Kinetics Inc. (NKI), the goggles incorporate many of the oculomotor, vestibular, and reaction-time tests that Hoffer helped NKI adapt from the company’s I-Portal Neuro-Otologic Test Center (NOTC). A sophisticated $250,000 rotary chair found in specialized balance centers, the I-Portal NOTC can measure concussion symptoms both initially and during recovery with 95 percent accuracy. The goggles, Hoffer says, can do about the same—in four minutes, at a fraction of the cost, at the site of the injury, and without an expert operator.

“The goggles are the future,” he predicts. “They will become the AEDs [automated external defibrillators] of the concussion world—with one at virtually every sideline, or locker room.”

Aside from their affordability and portability, the I-Portal PAS goggles, which could be on the market by next year, have another huge advantage. Nobody, not even elite athletes, can fool them. For an invisible injury that relies on self-reporting, in a culture that reveres and rewards strength, toughness, and perseverance, that’s critical.

“Many athletes don’t report their symptoms because it’s not a big deal,” Hotz says. “They have a headache, they take a Tylenol, and eventually they feel better. But too many athletes hide their symptoms for fear of being yanked from the game, or ruining their pro prospects. That’s a huge problem.”

A lifelong soccer player, David Goldstein wasn’t hiding anything when he played through what turned out to be his third concussion in four years during his freshman year at Ransom Everglades School in Miami.

When he collided head to head with an opposing player during the district finals in January 2010, he didn’t give it any thought. Filling in for an injured varsity player, the game was the biggest of his life. All he cared about was helping Ransom win, which it didn’t.

“You can see it on the video: I instantly put my hand to my head. I knew something was wrong, but it was a huge opportunity for me. I had a lot of adrenaline and the game mattered a ton,” Goldstein recalls.

The day after the match, Goldstein, who graduated from Princeton University in June and is pursuing a master’s degree in sports management at Columbia University, went to his club practice. He still had a headache but didn’t want to disappoint his coach. Afterward, he collapsed, wracked with pain that, along with nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, irritability, and exhaustion, would persist for four months, through visits to a number of doctors.

“They all suspected a concussion and they said the same thing: ‘You pass the standard neurological exams. We don’t know what else to do for you. Rest. Don’t play. Sorry,’” Goldstein says. “Then I found Drs. Hotz and Nedd, and within two weeks I was symptom-free. They asked me questions others hadn’t. They gave me medication others hadn’t, and they tested my balance, which I thought was strange.”

Hotz also administrated a 20-minute computerized neurocognitive test that would help confirm his diagnosis. Known as ImPACT—for Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing—the test is usually given to athletes in the preseason to establish a baseline for cognitive function in the event of a head injury. Hotz gave Goldstein, an excellent student, the test anyway, matching his results against an average student. His ImPACT scores were below average.

Determined to help other students avoid his ordeal, Goldstein and his parents launched a fundraising campaign for concussion awareness and testing in 2011, raising enough money to enable athletic trainers to administer the baseline test to every one of Miami-Dade’s 15,000 public high school student-athletes. This summer, the Miami Dolphins Foundation announced it would assume the cost of countywide baseline testing for Miami-Dade’s high school athletes, and eventually those in Broward and Palm Beach counties, too.

Goldstein also spearheaded the passage of the 2012 Florida law that bars youth athletes who exhibit concussion symptoms from returning to practice or play until a physician clears them. Proposed by a statewide concussion task force that Hotz led, the bill was signed into law at the Miller School by Governor Rick Scott, who dedicated it to Daniel Brett. The year before, Brett, a high school freshman from Broward County who dreamed of playing for the Miami Hurricanes, took his own life, ending two years of agony from multiple concussions.

Today, funded by the annual Daniel’s Dash for Concussion Awareness 5K Run/Walk in Sunrise, retired NFL wide receiver Ray Crittenden, a researcher on Hotz’s concussion team, visits area high schools to talk to football players about the consequences of ignoring concussion symptoms.

Crittenden knows he’s reaching some young men, but research shows most high school football players still do not report symptoms. “I’ll see some of these kids in the clinic, and they tell me, ‘You’re the reason I’m here,’ but the culture is embedded by high school,” he says. “We really need to start earlier, so they grow up in a culture of awareness.”

Fortunately, Crittenden says, Miami-Dade has a growing legion of sentinels—the hundreds of public high school coaches, athletics directors, and trainers who, through the state law and their training for and participation in the countywide concussion program, understand what Scavo began learning the night he met Hotz on Southridge High’s sidelines.

“Concussion is serious, and we all have to take it seriously,’’ says Scavo, who became UM’s head athletic trainer in 2011. “We are the frontlines, and now we have the tools to build awareness and change the culture.”

Now a model for the nation, the countywide program is also a valuable research tool, providing Hotz and her team the big-picture data on how and when youth athletes in all sports suffer concussions, and how long they take to recover. But it’s also an essential prevention tool, raising red flags about isolated problems. Hotz points to a high school that, over two weeks, sent seven football players to the concussion clinic. She soon learned why: None of them had been wearing their assigned, properly fitted helmets; they were just randomly grabbing one.

“To get a handle on injury prevention, you have to have a surveillance system in place that helps you look at where, when, why, and how injuries are happening,” Hotz says. “Now we have those answers, and can drill down to the problem and fix it. Maybe it’s the helmet; maybe it’s a tackling technique issue. Without surveillance, we wouldn’t know.”

And without Hotz, who also launched the countywide BikeSafe and statewide WalkSafe programs to teach youngsters to ride and cross streets safely, Florida might be a far riskier place to play contact sports.

“People ask me all the time if I would let my kid play football,” she says. “Absolutely I would. But I wouldn’t drop my kid off at a pool that didn’t have a certified lifeguard on duty. And I wouldn’t drop my kid off at a field to play without a coach or someone there who is trained in proper tackling techniques and who understands concussion.”

Follow

Follow